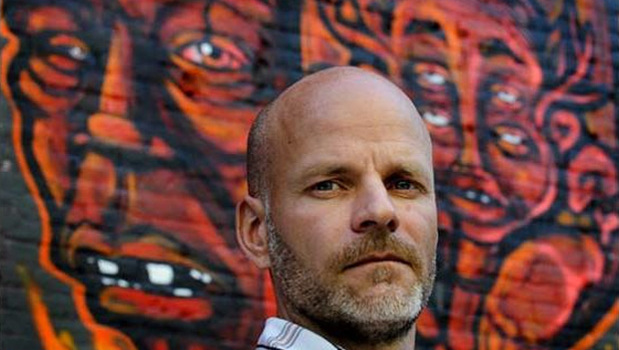

The Biz Interview: Kevin Miller – Director of “Hellbound?”

Kevin Miller is the Vancouver-based director of the thought-provoking new documentary, Hellbound?. Sure to inspire conversation and questions from viewers about what the concept of Hell may or may not represent, this project represents a bold step for Miller in his filmmaking career. He spoke with us about the film and shared some insights into what went into making the film.

Can you briefly walk us through your creative process for the production from the early stages (initial ideas, writing, etc.) all the way to the theatrical release?

For me, every project begins with a core idea or an image that eventually unpacks itself over time. On this project, it was simply a title—Hellbound?—which struck me after reading an article about hell in Maclean’s several years ago. Back then; it was merely going to be a comedic short film that asked people how likely they thought it was that they—or people they knew—were going to hell. That changed in the fall of 2008 when I edited a book on hell for a friend of mine named Brad Jersak. Called Her Gates Will Never Be Shut: Hope, Hell and the New Jerusalem, his book introduced me to a fascinating historical conversation about how to interpret what the Bible says about hell, a conversation that I wanted to translate into film.

But how to do that? This couldn’t simply be a “talking heads” academic debate, so I had to figure out ways to illustrate the concept of hell and the various perspectives on it. Thankfully, hell gives rise to all sorts of fascinating imagery, so that was very helpful. Hell is also a concept that has been interpreted and re-purposed in a variety of ways throughout the culture, such as in death metal music, so we had a lot to work with on that level as well.

From there, it was simply a matter of figuring out who were the most compelling characters in this debate, what situations would provide the most interesting observational footage, and then what sort of unifying image would help to tie everything together.

One of the most significant creative choices I made was to frame the entire conversation within the context of the 9/11 attacks on America. It just so happened that the tenth anniversary of that event coincided with our production schedule, so we went to New York to capture the raw emotion of that day. I think it serves as a powerful visual metaphor that helps us explore different perspectives on evil, suffering and justice, which is what I think the hell debate is really about.

Of course, the editing phase always causes you to see your film in a different way. They say every film gets written three times—once during pre-production, a second time during production and then a third time during editing. I couldn’t agree more. Once I started cutting the film, I realized that rather than a broad approach to the topic of hell; I needed to focus in on a specific conflict over the doctrine that was flaring up within the evangelical church. This microcosm became an effective way to explore not just hell but how we form beliefs and how we deal with people who disagree with us.

What themes and ideas do you want the audience to think about from watching the film?

On one level, this film is about a theological debate that is currently taking place within the evangelical church. But as I alluded to before, I think this film is just as interested in how this debate is taking place and the consequences of this debate not just for Christians but also for everyone else. What we believe—or don’t believe—about hell is not merely an abstract theological question. Every belief gives rise to real world consequences. So whether you believe in hell or not, I think you need to pay attention to what’s going on here, because it will affect you in some way. On another level, I hope the film prompts all of us to take a second look at what we believe, why we believe it and the effect our beliefs are having on the world. Also, how can we debate controversial topics without demonizing people who disagree with us? In the end, none of us really knows what happens after we die—if anything. But we can probably all agree that beliefs about the afterlife that cause us to be disagreeable people in this life are probably best set aside.

What was the most challenging sequence to film?

I’ll give two answers to this question. On a technical level, the most challenging event to film was the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. Lower Manhattan was in total lockdown mode, with whole sections of the city cordoned off and guarded by bomb-sniffing dogs, armored personnel carriers, guard towers and thousands of police officers with machine guns. At one point we thought there was no way we were going to be able to capture the footage we needed. But thankfully it occurred to us to capture our struggle to move through a city riveted in fear, because that footage plays a key role during the lowest point of the film.

On a personal level, the most difficult thing to film was a sequence that takes place at a “hell house”—a “ministry” put on every Halloween by a church in Dallas that uses hellish scenarios to scare people into becoming Christians. I just found the whole thing so morally repugnant that it took everything in me to finish the shoot that night. And I’m glad I did, because it allowed us to capture what I believe to be one of the most poignant moments in the film.

Which accomplishments are you most proud of from each filmmaking experience that you’ve had and what are the most important lessons you’ve learned?

Oh boy, I’ve worked on a number of films now, so it’s hard to remember what I learned when! But I will say this: Something every creative person desires is true authorship, the opportunity to see their vision through from start to finish with minimal interference from other people. That’s why so many screenwriters want to become directors, because even though the writer authors the script, the director authors the film. With Hellbound?, I can say I’ve been able to fulfill every creative person’s dream. I’ve been able to take this project all the way through from initial concept to funding, production, post-production and finally to theatrical release, which we are managing as well. I’ve been in the driver’s seat the entire way, making big creative decisions—such as who to interview, what moments to capture and so on—down to the smallest decisions, such as what sort of font to use on our web page. That’s not to say I’m a micro-manager or that I haven’t had a lot of help. I’ve had a fantastic team supporting me every step of the way, including my investor Dave Krysko, who has given me tremendous latitude to pursue my vision. So while there’s nothing like having full authorship of a project, this is also a highly collaborative business, and if you don’t “play well with others,” it’s not going to go well for you.

Who are your major inspirations for becoming a director?

At the top of my list is Werner Herzog. I can’t tell you how much I appreciate him as a person, let alone his films. I think every aspiring director should watch Burden of Dreams, which documents the making of Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo, which very nearly ended in disaster. Seeing him navigate one crisis after another and yet refuse to give up or lose his cool is truly inspirational. But apart from that, he is such a curious and thoughtful person, always gracious to the people he interviews and so adept at drawing out their personality. He has a hungry mind, and you sense he’s always probing for something beyond conscious awareness, for the essence of “what is.” I’d love to meet him one day. In fact, I have so much leftover footage from Hellbound? that I have this crazy idea of cutting it together into a film called Ode to Herzog. Stay tuned for that!

Another person whose work I really respect is Paul Thomas Anderson. Here’s a guy who is unafraid to stare into the abyss, but he still manages to hold onto hope. His images are so powerful, and he’s such a great storyteller on top of that. Magnolia and There Will Be Blood rank as two of my favorite films. They’re not easy to watch at times, but they penetrate so deep into the human experience that I can’t look away.

Of course, I also have to mention the Coen Brothers—particularly True Grit and No Country for Old Men—and Darren Aronofsky. Like Anderson, these filmmakers have somehow managed to create powerful, highly personal films within the studio system, and I really admire them for that.

What advice would you offer to aspiring directors who are looking to get started in the industry?

Don’t just talk about it; do it. I’ve learned more about filmmaking while shooting and editing spoof movie trailers with my kids than I have from any book. Watching movies and reading books about directing and storytelling is crucial, but don’t let that become a form of procrastination. There’s really no excuse not to be shooting constantly. Anyone with a smart phone can shoot a feature—in 1080p, no less—with little or no money.

So experience is one thing, but you also need to educate yourself. Go to film school if you can afford it, but once again, don’t think that having a degree makes you a filmmaker. I’ve never been to film school, and yet I’ve worked on more films than I can count. But I have spent thousands of hours reading, writing and experimenting with filming and editing techniques. I find a well-timed mistake can be the best learning experience of all.

The second part is networking. This is a relationship business, and you are only as good as your network. Most of the jobs I’ve gotten are through people I know. It’s that old adage about preparation meeting opportunity. The thing I find is that people want to jump right to opportunity. I find that if you prepare yourself well, opportunities tend to present themselves.

Which steps can directors take to build positive working relationships with their crew during the making of a film?

Even though the director is the author of the film, that doesn’t mean he or she doesn’t work with a number of “co-writers.” The way I see it, I want everyone on my crew to come away from the experience feeling like they weren’t just my hands and feet, so to speak; they truly contributed something creative to the process. So while I’m pretty clear about what I want in most instances, I’m always open to input from the crew. What do they want to take away from this experience? How can I facilitate that? And let’s be honest, on some days you’re simply so worn down you don’t know if you have it in you to continue. On those days, your crew can carry you through—but not if you’ve been abusing them every day up to that point. A film set can quickly turn into a poisonous atmosphere if grievances are allowed to fester, so I also work hard to resolve differences quickly.

What is the biggest obstacle facing independent filmmakers right now and how are you handling it?

Raising money, hands down. I handle it the same way every filmmaker does—knocking on doors until one finally opens. I was fortunate on Hellbound?, because I found a single investor who was willing to fund not only the film but also marketing and distribution. And he’s made a point of not interfering in the creative process, even though I have consulted with him at several key points along the way.

The thing is, I probably enjoy the business of filmmaking as much as I enjoy making the film itself, so pitching and promoting my idea comes quite naturally. Other filmmakers aren’t wired that way at all. So I encourage them to bring on a producer or some other partner who can help them pitch their project in a way that makes sense to investors. There really is no easy way to do it; but the better you are at selling your vision, the better your chances of seeing it realized.

Are there any books or specific authors that have been influential to you during your journey as a filmmaker?

Again, I come at this initially as a screenwriter, so I’m going to point to books like Story by Robert McKee, The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler and so on. But I’ve also learned a lot from books like Directing Shot by Shot and, believe it or not, a little book from the 1960s called How To Direct a Movie Story. I’m always reading director bios as well.

Are there any upcoming projects that you’re working on that you’d like to mention?

I have all sorts of things in the works, but something I’m most excited about is a Frank Schaeffer novel I’ve optioned called And God Called Billy… It’s a darkly comic, coming-of-age story about a young filmmaker who feels called to make “God’s movie” in Hollywood, only to have things go disastrously wrong, causing him to question everything he’s believed up to that point. I also have plans for more documentary films. I hope to be like Herzog one day, able to vacillate between documentaries and feature films according to whatever project I’m most passionate about at the time.

Hellbound? opens on Friday, October 12th in Vancouver before expanding to select Canadian cities. You can read more about the film at HellboundTheMovie.com.